Blockchain smart contracts: Applications, challenges, and future trends

In recent years, the rapid development of blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies has influenced the financial industry by creating a new crypto-economy. Then, next-generation decentralized applications without involving a trusted third-party have emerged thanks to the appearance of smart contracts, which are computer protocols designed to facilitate, verify, and enforce automatically the negotiation and agreement among multiple untrustworthy parties. Despite the bright side of smart contracts, several concerns continue to undermine their adoption, such as security threats, vulnerabilities, and legal issues. In this paper, we present a comprehensive survey of blockchain-enabled smart contracts from both technical and usage points of view. To do so, we present a taxonomy of existing blockchain-enabled smart contract solutions, categorize the included research papers, and discuss the existing smart contract-based studies. Based on the findings from the survey, we identify a set of challenges and open issues that need to be addressed in future studies. Finally, we identify future trends.

Similar content being viewed by others

A Review on Blockchain Smart Contract Applications

Chapter © 2023

Smart Contracts: A Way to Modern Digital World

Chapter © 2022

Smart Contracts – Blockchains in the Wings

Chapter © 2018

Explore related subjects

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

For more than a decade, the blockchain is established as a technology where a distributed database records all the transactions that have happened in a peer-to-peer network. It is regarded as a distributed computing paradigm that successfully overcomes the issue related to the trust of a centralized party. Thus, in a blockchain network, several nodes collaborate among them to secure and maintain a set of shared transaction records in a distributed way without relying on any trusted party. In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto introduced Bitcoin [69] that was the first proposed cryptocurrency introducing the blockchain as a distributed infrastructural technology. It allowed users to transfer securely crypto-currencies, known as “bitcoins” without a centralized regulator. Besides, Ethereum [16], NXT [71], and Hyperledger Fabric [4] were also proposed as blockchain-based systems used for the cryptocurrency. Unlike Bitcoin, they can use smart contracts (SC). Blockchain technology overlaps traditional contracts by including the terms of agreements between two or more parties, but surpasses them thanks to smart contracts by automating the execution of agreements in a distributed environment when conditions are met.

Smart contracts are executable codes that run on top of the blockchain to facilitate, execute, and enforce an agreement between untrustworthy parties without the involvement of a trusted third-party [16]. Smart contracts gave network automation and the ability to convert paper contracts into digital contracts. Compared to traditional contracts, smart contracts enabled users to codify their agreements and trust relations by providing automated transactions without the supervision of a central authority [89]. In order to prevent contract tampering, smart contracts are copied to each node of the blockchain network. By enabling the execution of the operations by computers and services provided by blockchain platforms, human error could be reduced to avoid disputes regarding such contracts.

Although smart contracts have made progress in recent years, they still face many challenges. For instance, one infamous malicious attack took place in 2016 when the Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) smart contract was manipulated to steal around 2 Million Ether Footnote 1 (50 Million USD on the time) because of its re-entrancy vulnerability [103]. In addition to the vulnerability problem, smart contracts face several challenges including privacy, legal, and performance issues.

To understand current topics on smart contracts, we conduct a comprehensive survey, with the aim of better identifying and mapping research areas that need further studies. The focus of this survey is studying smart contracts from the technical point of view (e.g., codifying, security, performance issues) and the usage point of view (e.g., smart contract applications in finance, healthcare, etc). The major contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

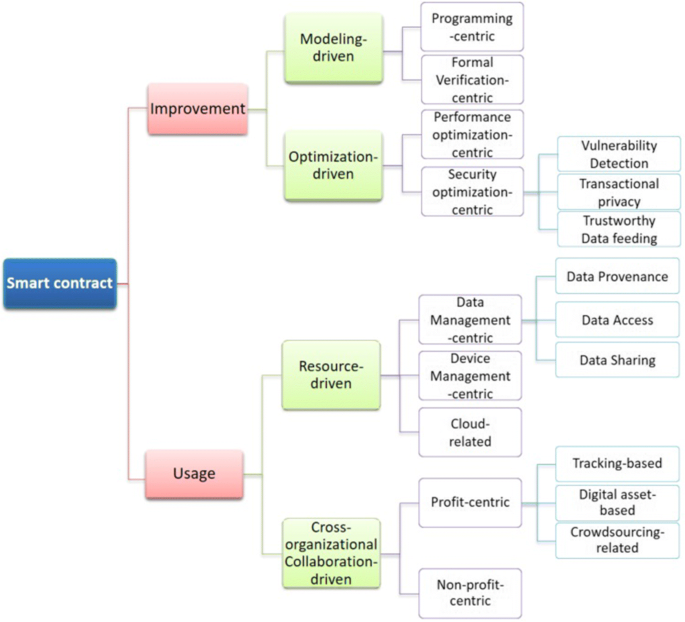

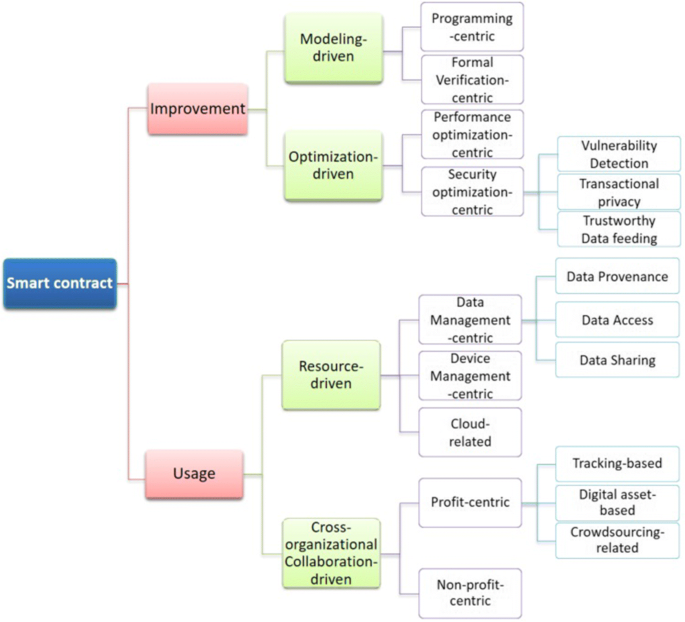

- 1. We propose a taxonomy of studies based on blockchain-enabled smart contracts including two categories, namely SC improvement and SC usage.

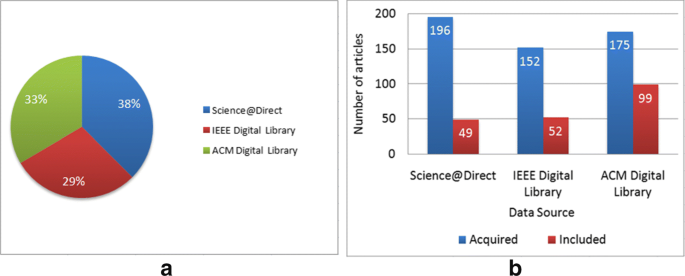

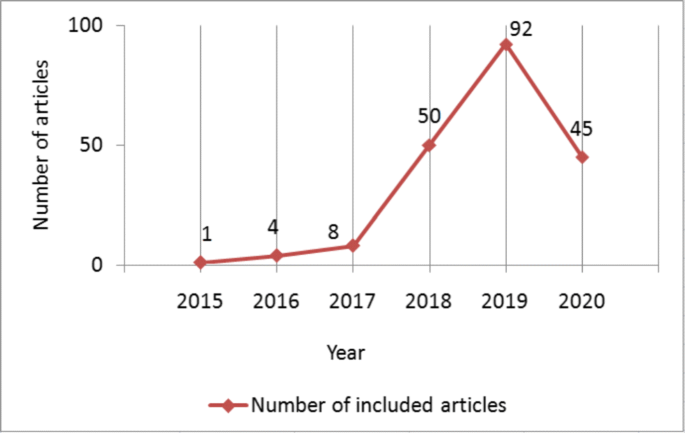

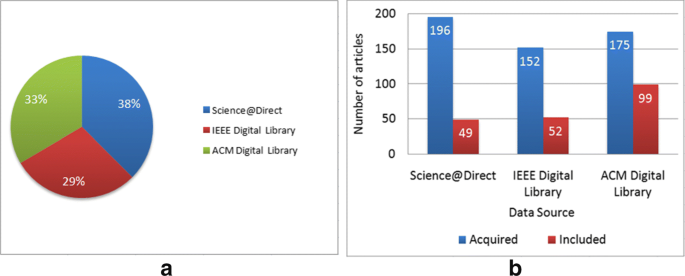

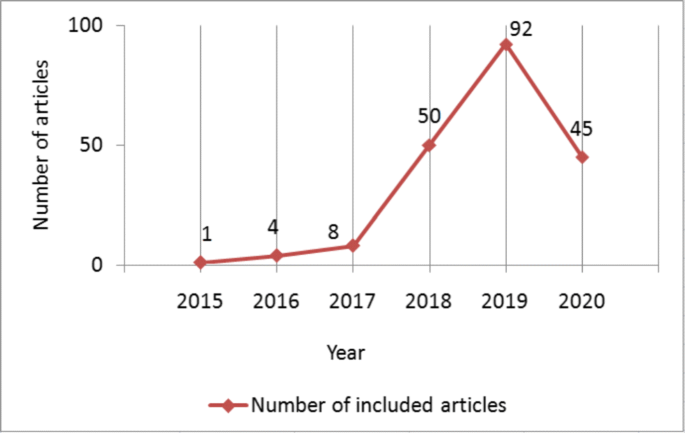

- 2. We categorize 200 papers that we have extracted from different digital databases and discuss the existing smart contract-based studies.

- 3. Based on the findings from the survey, we identify a set of smart contract challenges and open issues that need to be addressed in future studies. Therefore, this survey provides a helpful reference to the researchers who want to target smart contract improvement or usage in their future studies.

- 4. Finally, we discuss future trends of smart contracts and explain how they provide better solutions to the open research challenges.

Considering the above contributions, the remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses background information about blockchain and smart contracts technologies. Section 3 discusses existing reviews studying smart contract-based approaches. Section 4 describes the adopted survey methodology and the solution taxonomy used to categorize existing smart contract-based solutions. In Sections 5–8, we present existing advances in modeling-driven smart contract improvement, optimization-driven smart contract improvement, resource-driven smart contract usage, and cross-organizational collaboration-driven smart contract usage. Section 9 discusses the study results by introducing challenges and future trends in the studied field. Finally, Section 10 concludes the paper.

2 Background

As aforementioned, blockchain technology has emerged as a distributed computing paradigm that successfully overcomes the problem related to the trust of a centralized party. Thus, in a blockchain network, several nodes collaborate among them to secure and maintain a set of shared transaction records in a distributed way without relying on any trusted party. Specific nodes in the network known as miners are responsible for adding new blocks to a distributed public ledger known as the blockchain.

The first system was Bitcoin [69], which allowed users to transfer securely the currency (bitcoins) without a centralized regulator. In the blockchain network, miners are responsible for collecting transactions, solving challenging computational puzzles (proof-of-work) in order to reach consensus, and adding the transactions as blocks to the blockchain. Since then, several blockchain-based development platforms have been proposed offering the ability to host/ use smart contracts to execute automatically events and actions., namely NXT [71], Ethereum [16], Hyperledger Fabric [4], etc.

We detail below the smart contract operational process and then discuss some blockchain platforms that support the development of smart contracts.

2.1 Operational process of smart contracts

A smart contract is a common agreement between two or more parties. It stores information, processes inputs, and writes outputs thanks to its pre-defined functions [16]. For instance, the smart contract can define the constructor function that enables the smart contract creation. Hosting a new smart contract in the blockchain is enabled by invoking the constructor function through a transaction, whose sender becomes the smart contract owner. A self-destruct function is another example of the functions that can be defined in a smart contract. Usually, only the smart contract owner can destruct the contract by invoking this function.

A smart contract is likely to be a class that includes state variables, functions, function modifiers, events, and structures [16] which is intended to execute and control relevant events and actions according to the contract terms. Besides, it can even call other smart contracts. Each smart contract includes states and functions. The former are variables that hold some data or the owner’s wallet address (i.e., the address in which the smart contract is deployed). We can distinguish between two state types, namely constant states, which can never be changed, and writable states, which save states in the blockchain. The latter are pieces of code that can read or modify states. We can distinguish between two function types, namely read-only functions, which do not require gas Footnote 2 to run and write functions that require gas because the state transitions must be encoded in a new block of the blockchain. Furthermore, paying currency is required to avoid infinitely smart contract runs.

As aforementioned, a smart contract is hosted in the blockchain by invoking its constructor function through a transaction submitted to the blockchain network, then the constructor function is executed, and the final code of the smart contract is stored on the blockchain. Once deployed, the creator of the smart contract got the returned parameters (e.g., contract address), then users can invoke any available smart contract’s function by sending a transaction.

2.2 Platforms for Smart Contracts

Smart contracts can be developed and deployed in different blockchain platforms (e.g., NXT, Ethereum, and Hyperledger Fabric). Several platforms offer distinctive features for developing smart contracts including contract programming languages, contract code execution, and security levels. Some platforms support high-level programming languages to develop smart contracts.

- Bitcoin [69] is a public blockchain platform that can be used to process cryptocurrency transactions, but with a very limited computing capability. Bitcoin uses a stack-based bytecode scripting language. The ability to create a smart contract with rich logic using the Bitcoin scripting language is very limited. Major changes would need to be made to both the mining functions and the mining incentivization schemes to enable smart contracts proper on Bitcoin’s blockchain [52].

- NXT [71] is an open-source blockchain platform that relies entirely on a proof-of-stake consensus protocol. It includes a selection of smart contracts that are currently living. However, it is not Turing-complete, meaning only the existing templates can be used and no personalized smart contract can be deployed.

- Ethereum [16] is the first blockchain platform for developing smart contracts. It supports advanced and customized smart contracts with the help of a Turing-complete virtual machine, called the Ethereum virtual machine (EVM). EVM is the runtime environment for smart contracts, and every node in the Ethereum network runs an EVM implementation and executes the same instructions. Solidity, as a high-level programming language, is used to write smart contracts, and the contract code is compiled down to EVM bytecode and deployed on the blockchain for execution. Ethereum is currently the most popular development platform for smart contracts and can be used to design various kinds of decentralized applications (DApps) in several domains.

- Rather than the public blockchain, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum that any party can participate in the network, Hyperledger Fabric [4] is permissioned with only a collection of business-related organizations can join in through a membership service provider, and its network is built up from the peers whose are owned and contributed by those organizations. Hyperledger Fabric is an open-source enterprise-grade distributed ledger technology platform, proposed by IBM and supports smart contracts. It offers modularity and versatility for a broad set of industry use cases. The modular architecture for Hyperledger Fabric accommodates the diversity of enterprise use cases through plug and play components.

Ethereum and Hyperledger Fabric smart contracts differ in multiple aspects. While Solidity is the well-known programming language used to write Ethereum smart contracts, Hyperledger Fabric supports multi-language smart contracts, such as Go, Java, and Javascript [4]. For contract code execution, the contract code in Ethereum is included in a transaction, which is propagated in the peer-to-peer network, and any miner that receives this transaction can execute it in its local virtual machine [16]. In Hyperledger Fabric, when a transaction is created by the application, the transaction is only executed and signed by specified peers (endorsing peers). After receiving the application’s transaction proposal, each of these endorsing peers independently executes it by invoking the chain-code to which the transaction refers [4]. For security, chaincode runs within a container environment (e.g., Docker) for isolation.

These blockchain-based development platforms are used in the existing studies that we detail in the following sections.

3 Related literature reviews/surveys

We provide a brief overview of the existing reviews that have studied blockchain-enabled smart contracts.

While several literature reviews/surveys are published in order to study the blockchain-enabled smart contracts, there are still some ongoing challenges that have not been addressed. Table 1 presents a comparative summary of the existing blockchain-enabled smart contract reviews/surveys according to six criteria, namely proposing a taxonomy, considering several blockchain platforms, considering application domains, covering smart contract improvement tools, identifying research gaps, and scope of literature review. We observe that there is a lack of taxonomy focusing on smart contract improvement (i.e., addressing smart contract security, privacy, and performance issues) and smart contract usage (i.e., addressing domain-specific issues).

To choose the relevant papers to be analyzed in our review, we filtered the primary studies retrieved from the databases. To do so, we defined a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria, which are summarised in Table 2. Based on the outcomes of the first phase, we applied the set of inclusion and exclusion criteria to exclude the publications considered outside the scope of this review. Thus, we only included studies that satisfy all the inclusion criteria. We excluded duplicate publications, surveys, and literature reviews by filtering studies based on the title, the abstract, and the list of keywords.

As a result of an in-depth analysis of the included studies in this review, a comprehensive taxonomy is constructed to provide an additional support for designers to understand the various dimensions that they have to consider when designing a smart contract. The major motivations of this survey are to identify (i) the main publications about smart contracts, (ii) the current state of research in this field, and (iii) possible gaps in the literature that could become research problems to be solved by the scientific community. Through this survey, we aspire not only to define the conceptual background of blockchain-enabled smart contracts, but also to identify research issues to be explored at new studies. Indeed, we categorize existing smart contract research into two major categories, namely smart contract improvement and smart contract usage. The former includes studies aiming at addressing the smart contract challenges, such as functionality verification, performance, vulnerabilities, and lack of trustworthy data feeding. The latter includes studies aiming at addressing domain-specific challenges using smart contracts. Figure 3 depicts the proposed taxonomy of blockchain-enabled smart contracts, including modeling-driven smart contract improvement (see Section 5), optimization-driven smart contract improvement (see Section 6), resource-driven smart contract usage (see Section 7), and cross-organizational collaboration-driven smart contract usage (see Section 8).

5 Modeling-driven smart contract improvement

Smart contracts have suffered from multiple security vulnerabilities in the past few years [8], which have resulted in both theft and gigantic financial losses. Such vulnerabilities could have been avoided with the help of formal analysis and verification of such smart contracts before deploying them on the blockchain. Since existing programming languages, such as Solidity are not built for formal verification, several researchers have proposed alternative approaches in order to improve the smart contract functionality verification. In this category, we discussed modeling-driven smart contract improvement solutions, which can be categorized into programming-centric solutions (see Table 3) and formal verification-centric solutions (see Table 4).

9.1.1 Legal issues

The legal issue of smart contracts is another crucial aspect of smart contract challenges. For example, the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [35] stipulates that citizens have a “right to be forgotten” which is inconsistent with the immutable nature of blockchain-enabled smart contracts. Other legal issues can be cited including, (i) each country has its own laws and regulations, hence, it is complicated to ensure compliance will all regulations, (ii) law clauses or conditions are not quantifiable, thus it is still complicated to model these conditions in smart contracts so that they are appropriate and quantifiable for a machine to execute them, and (iii) governments are interested in a regulated and controlled use of the blockchain technology in many applications, however, this means that the untrustworthy network will regress to a third-party trusted network, losing part of its essence [79].

9.1.2 Reliance on “off-chain” Resources

Several smart contracts require receiving information or parameters from resources that are not on the blockchain itself, so-called off-chain resources. For this purpose, oracles are used as trusted third parties that retrieve off-chain information and then push that information to the blockchain at predetermined times. Although existing oracles are well tested, their use may introduce a potential “point of failure”. For instance, an oracle might be unable to push out the necessary information, provide erroneous data, or go out of business. Therefore, smart contracts will need to account for these eventualities before their adoption can become more widespread [51].

9.1.3 Immutability issue

The immutability feature is an important characteristic of smart contracts. Indeed, once a smart contract is deployed, the code cannot be changed by any party. However, the dark side of the immutability concept in smart contracts lies mainly in the fact that in the event of any errors made in the code, the immutability feature of a smart contract prevents it from being rectified. Similarly, if circumstances change (e.g., the parties have mutually agreed to change the parameters of their business deal, or if there is a change in law, etc.), no simple path to amend a smart contract is possible. Therefore, extensive and possibly expensive reviews of the smart contract performed by experts before its deployment in a blockchain are required to address the immutability issue.

Another limitation in the blockchain itself that impacts the smart contracts is the irreversible nature of the blockchain, thus once the smart contracts are deployed, they cannot be changed. Moreover, any blockchain nodes can be hacked or misused to report erroneous data that will be logged on the blockchain in an immutable manner.

9.1.4 Scalability issue

Scalability is the primary concern for many blockchain networks. For instance, the Ethereum blockchain can verify 14 transactions per second, which is slow as compared with Visa that can handle up to 24,000 transactions per second. Indeed, the scalability issue leads to network congestion, increased commission fees for transactions, and an increase in the time required to confirm the transactions [80]. In order to address the scalability issue, extensive research focusing on increasing the number of transactions per second by smart contract platforms is required in the future. However, the transaction verification depends on the consensus mechanism used by the smart contract platforms. Therefore, scalability depends on consensus mechanisms, which is another issue in smart contracts.

9.1.5 Consensus mechanism issue

The consensus mechanism plays the leading role to maintain security, scalability, and decentralization in the blockchain networks at the same time. There are several existing consensus algorithms, including Proof-of-Work (PoW), Proof-of-Stake (PoS), etc. Although the PoW algorithm enables security in the blockchain, it wastes resources. Thus, many organizations switch from the PoW algorithm to new consensus mechanisms that promise lower fees for transactions as well as lower energy costs for the block production process. Therefore, future studies can use new consensus mechanisms, such as proof-of-activity (PoA) or delegated proof-of-stake (DPoS) in order to test them and eventually improve their quality.

9.2 Future Development Trends

Future development trends of smart contracts are introduced from two aspects namely, Layer 2 protocols, and contract management solutions.

9.2.1 Layer 2 protocols

In order to address the aforementioned challenges faced by smart contracts, a viable solution, called Layer 2 is appeared to tackle the blockchain scalability problem. While Layer 1 is the used term to describe the underlying main blockchain architecture, Layer 2 is an overlaying network that lies on top of the underlying blockchain. Indeed, Layer 2 refers to the multiple solutions or protocols being built on top of an existing blockchain system. The main goal of Layer 2 protocols is to solve the transaction speed and scaling difficulties that are being faced by the major cryptocurrency networks. Therefore, Layer 2 protocols refer to a secondary framework, where blockchain transactions and processes can take place independently of Layer 1 (“main-chain”). Two major examples of Layer 2 solutions are the Bitcoin Lightning Network [27] and the Ethereum Plasma [76]. The Lightning Network, which in part developed at the MIT Media Lab’s Digital Currency Initiative, is a lightweight software solution for scaling public blockchains and cryptocurrency interoperability. It aims at greatly reducing cost and time constraints by shifting small transactions to a cryptographically secure “off-chain” environment so that only large netting transactions need to be directly settled into a resource-constrained blockchain [27]. Ethereum Plasma is a series of smart contracts, which allows for many blockchains within a root blockchain. The root blockchain enforces the state in the Plasma chain. The root chain is the enforcer of all computation globally but is only computed and penalized if there is proof of fraud. Many Plasma blockchains can co-exist with their business logic and smart contract terms. Indeed, Plasma enables persistently operating decentralized applications at a high scale [76]. To sum up, thanks to Layer 2, a great portion of the work that would be performed by the “main-chain” can be moved to the second layer. So while the “main-chain” provides security, the second layer protocols provides better solutions for the scalability issue by offering high throughput, being able to perform hundreds, or even thousands, of transactions per second.

9.2.2 Contract management solutions

Smart contracts encompass far more than just the benefits of blockchain technology. Rather, the term captures the entire digital life cycle of a contract, from negotiation to control and verification of the fulfillment of contractual obligations. Now, it is already possible to use smart contracts even without blockchain technology. Thus, contract management solutions could overcome both the immutability issue and the irreversible nature of blockchain by handling the contract’s life-cycle while eliminating limitations of the technology itself. In state-of-the-art contract management solutions [31], all parties to the contract must provide proof of identity and authenticate their access to data in order to ensure the basis of trust. Besides, all documents that are associated with the contract are stored in a revision-secure manner and encrypted form on a cloud-based platform developed and operated in Europe. This ensures transparency and traceability for all events, the actions associated with these events, and the designation of the persons responsible [23]. For instance, Fabasoft Contracts [31] is one of the latest contract management solutions that is ready-to-use, cloud-based software to support users throughout the entire contract life cycle: from cross-company contract preparation, efficient handling of review and approval processes, to the revision-secure contract archiving. It enables the modeling of contract rights and obligations, which can be automatically verified and enforced. There are several benefits offered by revision-secure contract management, including providing traceability when monitoring the cold chain of food delivery or proving the authenticity of spare automotive parts, as opposed to counterfeit articles [23].

10 Conclusion

The decentralization, auto-enforcing ability, and verifiability characteristics of smart contracts enable their encoded business rules to be executed in a peer-to-peer network, where each node is “equal” and none has any special authority without the involvement of a trusted authority or a central server. Thus, smart contracts are expected to revolutionize many traditional industries, such as financial, healthcare, energy, etc. In this paper, we presented a comprehensive survey of blockchain-enabled smart contracts from both technical and usage points of view. Thus, we introduced a taxonomy of existing blockchain-enabled smart contract solutions, categorized the included research papers, and discussed the existing smart contract-based studies. Based on the findings from the survey, both smart contract challenges and open issues are identified to be addressed in further studies. Finally, we discussed future trends of smart contracts. This study provides informational support to stakeholders interested in the research of smart contracts.

Notes

Ether (ETH): the cryptocurrency of Ethereum apps that is digital, global money.

gas: a unit that measures the amount of computational effort that it will take to execute certain operations.

References

- Alharby M, Aldweesh A, van Moorsel A (2018) Blockchain-based smart contracts: A systematic mapping study of academic research (2018). In: 2018 International Conference on Cloud Computing, Big Data and Blockchain (ICCBB), IEEE, pp 1–6

- Amani S, Bégel M, Bortin M, Staples M (2018) Towards verifying ethereum smart contract bytecode in isabelle/hol. In: Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Certified Programs and Proofs. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 66–77

- Analytics TC Ripple xrp continue to revolutionize cross border payment systems. Available online at https://thecurrencyanalytics.com/11696/ripple-xrp-continue-to-revolutionize-cross-border-payment-systemshttps://thecurrencyanalytics.com/11696/ripple-xrp-continue-to-revolutionize-cross-border-payment-systems (2020). Last accessed: 2020-10-03

- Androulaki E, Barger A, Bortnikov V, Cachin C, Christidis K, De Caro A, Enyeart D, Ferris C, Laventman G, Manevich Y et al (2018) Hyperledger fabric: A distributed operating system for permissioned blockchains. In: Proceedings of the Thirteenth EuroSys Conference, ACM, pp 30

- Angelo MD, Salzer G (2019) A survey of tools for analyzing ethereum smart contracts. In: IEEE International Conference on Decentralized Applications and Infrastructures, DAPPCON 2019, newark, CA, USA, April 4-9, 2019, IEEE, pp 69–78

- Angrish A, Craver B, Hasan M, Starly B (2018) A case study for blockchain in manufacturing: “fabrec”: A prototype for peer-to-peer network of manufacturing nodes. Procedia Manufacturing 26:1180–1192. 46th SME North American Manufacturing Research Conference, NAMRC 46, Texas, USA ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Asgaonkar A, Krishnamachari B (2019) Solving the buyer and seller’s dilemma: A dual-deposit escrow smart contract for provably cheat-proof delivery and payment for a digital good without a trusted mediator. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC)

- Atzei N, Bartoletti M, Cimoli T (2017) A survey of attacks on ethereum smart contracts (sok). In: International Conference on Principles of Security and Trust, Springer, pp 164–186

- Bader L, Bürger JC, Matzutt R, Wehrle K (2018) Smart contract-based car insurance policies. In: 2018 IEEE Globecom workshops (GC wkshps), pp 1–7

- Bai X, Cheng Z, Duan Z, Hu K (2018) Formal modeling and verification of smart contracts. In: Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 322–326

- Baralla G, Pinna A, Corrias G (2019) Ensure traceability in european food supply chain by using a blockchain system. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Emerging Trends in Software Engineering for Blockchain, IEEE Press, pp 40–47

- Bartoletti M, Pompianu L (2017) An empirical analysis of smart contracts: Platforms, applications, and design patterns. In: International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Springer, pp 494–509

- Bertini T, Butkute K, Canessa F Smart flight insurance—insureth. Available online at http://mkvd.s3.amazonaws.com/apps/InsurEth.pdf (2015). Last accessed: 2020-10-10

- Bogner A, Chanson M, Meeuw A (2016) A decentralised sharing app running a smart contract on the ethereum blockchain. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on the Internet of Things. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 177–178

- Bragagnolo S, Rocha H, Denker M, Ducasse S (2018) Smartinspect: Solidity smart contract inspector. In: 2018 International workshop on blockchain oriented software engineering (IWBOSE), pp 9–18

- Buterin V et al (2014) A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform. White paper

- Casado-Vara R, Prieto J, [la Prieta] FD, Corchado JM (2018) How blockchain improves the supply chain: Case study alimentary supply chain. Procedia Comput Sci 134:393–398. The 15th International Conference on Mobile Systems and Pervasive Computing (MobiSPC 2018) / The 13th International Conference on Future Networks and Communications (FNC-2018) / Affiliated Workshops ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chen T, Li Z, Zhou H, Chen J, Luo X, Li X, Zhang X (2018) Towards saving money in using smart contracts. In: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Software Engineering: New Ideas and Emerging Results. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 81–84

- Cheng S, Shi W, Zhang H (2019) Voltimebank: A volunteer system for mutual pension based on blockchain. In: Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Blockchain Technology. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 75–79

- Ciocarlie G, Eldefrawy K, Lepoint T (2018) Blockcis—a blockchain-based cyber insurance system. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering (IC2E), Orlando, FL, USA, pp 17–20

- Cuccuru P (2017) Beyond bitcoin: An early overview on smart contracts. I J Law Inform Technol 25(3):179–195 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dagher GG, Mohler J, Milojkovic M, Marella PB (2018) Ancile: Privacy-preserving framework for access control and interoperability of electronic health records using blockchain technology. Sustainable Cities and Society 39:283–297 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dangl A Top trends 2020: Hyperautomation and smart contracts. Available online at https://www.fabasoft.com/en/news/blog/top-trends-2020-hyperautomation-and-smart-contracts (2019). Last accessed: 2020-10-07

- Dasaklis TK, Casino F, Patsakis C (2019) Defining granularity levels for supply chain traceability based on iot and blockchain. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Omni-Layer Intelligent Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 184–190

- DHarz D, Knottenbelt W (2018) Towards safer smart contracts: A survey of languages and verification methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.09805

- Dickerson T, Gazzillo P, Herlihy M, Koskinen E (2019) Adding concurrency to smart contracts. Distrib Comput 33:1–17 MathSciNetMATHGoogle Scholar

- Dryja T, Glasbergen G-J, Lovejoy J Layer 2 - the lightning network. Available online at https://dci.mit.edu/lightning-network/ (2019). Last accessed: 2020-10-20

- Dziembowski S, Eckey L, Faust S (2018) Fairswap: How to fairly exchange digital goods. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 967–984

- Ellul J, Pace GJ (2018) Alkylvm: A virtual machine for smart contract blockchain connected internet of things. In: 2018 9Th IFIP International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security (NTMS), pp 1–4

- Eltayieb N, Elhabob R, Hassan A, Li F (2020) A blockchain-based attribute-based signcryption scheme to secure data sharing in the cloud. J Syst Archit 102:101653 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fabasoft: Fabasoft contracts. Available online at https://www.fabasoft.com/en/products/fabasoft-contracts (2020). Last accessed: 2020-10-07

- Farooq MS, Khan M, Abid A (2020) A framework to make charity collection transparent and auditable using blockchain technology, vol 83

- Feng X, Wang Q, Zhu X, Wen S (2019) Bug searching in smart contract. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.00799

- Gao Z, Xu L, Chen L, Shah N, Lu Y, Shi W (2017) Scalable blockchain based smart contract execution. In: 2017 IEEE 23Rd international conference on parallel and distributed systems (ICPADS), pp 352–359

- GDPR (2016) Regulation (eu) 2016/679 of the european parliament and of the council of 27 april 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing directive 95/46. Official Journal of the European Union (OJ) 59:1–88 Google Scholar

- Guo H, Meamari E, Shen CC (2019) Multi-authority attribute-based access control with smart contract. In: Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Blockchain Technology. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 6–11

- Gupta R, Tanwar S, Al-Turjman F, Italiya P, Nauman A, Kim SW (2020) Smart contract privacy protection using ai in cyber-physical systems: Tools, techniques and challenges. IEEE Access 8:24746–24772 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Han S, Xu Z, Zeng Y, Chen L (2019) Fluid: A blockchain based framework for crowdsourcing. In: Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Management of Data. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 1921–1924

- Hasan H, AlHadhrami E, AlDhaheri A, Salah K, Jayaraman R (2019) Smart contract-based approach for efficient shipment management. Comput Ind Eng 136:149–159 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hu VC, Ferraiolo D, Kuhn R, Friedman AR, Lang AJ, Cogdell MM, Schnitzer A, Sandlin K, Miller R, Scarfone K et al (2013) Guide to attribute based access control (abac) definition and considerations (draft). NIST special publication 800(162):1–54 Google Scholar

- Hu Y, Liyanage M, Mansoor A, Thilakarathna K, Jourjon G, Seneviratne A (2018) Blockchain-based smart contracts-applications and challenges. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04699

- Hwang GH, Tien PC, Tang YH (2020) Blockchain-based automatic indemnification mechanism based on proof of violation for cloud storage services. In: Proceedings of the 2020 The 2nd International Conference on Blockchain Technology. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 90–94

- Islam MN, Kundu S (2019) Enabling ic traceability via blockchain pegged to embedded puf. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst 24(3):1–23 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Javaid U, Aman MN, Sikdar B (2018) Blockpro: Blockchain based data provenance and integrity for secure iot environments. In: Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Blockchain-Enabled Networked Sensor Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 13–18

- Javaid U, Siang AK, Aman MN, Sikdar B (2018) Mitigating lot device based ddos attacks using blockchain. In: Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Cryptocurrencies and Blockchains for Distributed Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 71–76

- Jentzsch C (2016) Decentralized autonomous organization to automate governance. White paper

- Jiang B, Liu Y, Chan WK (2018) Contractfuzzer: Fuzzing smart contracts for vulnerability detection. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Automated Software Engineering. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 259–269

- Kolluri A, Nikolic I, Sergey I, Hobor A, Saxena P (2019) Exploiting the laws of order in smart contracts. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 363–373

- Kosba A, Miller A, Shi E, Wen Z, Papamanthou C (2016) Hawk: The blockchain model of cryptography and privacy-preserving smart contracts. In: 2016 IEEE Symposium on security and privacy (SP), IEEE, pp 839–858

- Leng J, Jiang P, Xu K, Liu Q, Zhao JL, Bian Y, Shi R (2019) Makerchain: A blockchain with chemical signature for self-organizing process in social manufacturing. J Clean Prod 234:7676778 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Levi SD, Lipton AB (2018) An introduction to smart contracts and their potential and inherent limitations. In: Harvard law school forum on corporate governance & financial regulation

- Lewis A A gentle introduction to smart contracts. Available online at https://bitsonblocks.net/2016/02/01/gentle-introduction-smart-contracts/https://bitsonblocks.net/2016/02/01/gentle-introduction-smart-contracts/ (2016). Last accessed: 2020-10-07

- Lin J, Shen Z, Zhang A, Chai Y (2018) Blockchain and iot based food traceability for smart agriculture. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Crowd Science and Engineering. Association for Computing Machinery, New York

- Liu C, Liu H, Cao Z, Chen Z, Chen B, Roscoe B (2018) Reguard: Finding reentrancy bugs in smart contracts. In: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceeedings. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 65–68

- Liu H, Zhang Y, Zheng S, Li Y (2019) Electric vehicle power trading mechanism based on blockchain and smart contract in v2g network. IEEE Access 7:160546–160558 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Liu J, Liu Z (2019) A survey on security verification of blockchain smart contracts. IEEE Access 7:77894–77904 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Liu X, Muhammad K, Lloret J, Chen YW, Yuan SM (2019) Elastic and cost-effective data carrier architecture for smart contract in blockchain. Futur Gener Comput Syst 100:590–599 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Loukil F, Ghedira-Guegan C, Boukadi K, Benharkat AN (2018) Towards an end-to-end iot data privacy-preserving framework using blockchain technology. In: International Conference on Web Information Systems Engineering. Springer, Berlin, pp 68–78

- Luu L, Chu DH, Olickel H, Saxena P, Hobor A (2016) Making smart contracts smarter. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 254–269

- Macrinici D, Cartofeanu C, Gao S (2018) Smart contract applications within blockchain technology: A systematic mapping study. Telematics Inform 35(8):2337–2354 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Maesa DDF, Mori P, Ricci L (2019) A blockchain based approach for the definition of auditable access control systems. Computers & Security 84:93–119 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Memoria F Smartbillions challenges hackers with 1,500 ether reward, gets hacked and pulls most of it out. Available online at https://www.ccn.com/smartbillions-challenges-hackers-1500-ether-reward-gets-hacked-pulls/https://www.ccn.com/smartbillions-challenges-hackers-1500-ether-reward-gets-hacked-pulls/ (2017). Last accessed: 2020-10-20

- Meng W, Wang J, Wang X, Liu J, Yu Z, Li J, Zhao Y, Chow SS (2018) Position paper on blockchain technology: Smart contract and applications. In: International Conference on Network and System Security, Springer, pp 474–483

- Meskini F, Islamic RA (2019) Multi-agent based simulation of a smart insurance using blockchain technology. In: 2019 Third International Conference on Intelligent Computing in Data Sciences (ICDS), IEEE, pp 1–6

- Missier P, Bajoudah S, Capossele A, Gaglione A, Nati M (2017) Mind my value: A decentralized infrastructure for fair and trusted iot data trading. In: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on the Internet of Things. Association for Computing Machinery, New York

- Mohanta BK, Panda SS, Jena D (2018) An overview of smart contract and use cases in blockchain technology. In: 9Th international conference on computing, communication and networking technologies, ICCCNT 2018, bengaluru, india, july 10-12, 2018, IEEE, pp 1–4

- Muneeza A, Arshad NA, Arifin AT et al (2018) The application of blockchain technology in crowdfunding: Towards financial inclusion via technology. Int J Manag Appl Res 5(2):82–98 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Murray Y, Anisi DA (2019) Survey of formal verification methods for smart contracts on blockchain. In: 10Th IFIP international conference on new technologies, mobility and security, NTMS 2019, canary islands, spain, june 24-26, 2019, IEEE, pp 1–6

- Nakamoto S Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Available online at https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (2008). Last accessed: 2020-10-20

- Nizamuddin N, Salah K, Azad] MA, Arshad J, Rehman M (2019) Decentralized document version control using ethereum blockchain and ipfs. Comput Electr Eng 76:183–197 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nxt community: Nxt whitepaper. Available online at https://nxtdocs.jelurida.com/Nxt_Whitepaper (2016). Last accessed: 2020-10-07

- Omar AA, Bhuiyan MZA, Basu A, Kiyomoto S, Rahman MS (2019) Privacy-friendly platform for healthcare data in cloud based on blockchain environment. Futur Gener Comput Syst 95:511–521 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Osterland T, Rose T (2020) Model checking smart contracts for ethereum. Pervasive and Mobile Computing 63:101129 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ouaddah A, Elkalam AA, Ouahman AA (2017) Harnessing the power of blockchain technology to solve iot security & privacy issues. In: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Internet of Things, Data and Cloud Computing, ICC’17. Association for Computing Machinery, New York

- Panja S, Bag S, Hao F, Roy B (2020) A smart contract system for decentralized borda count voting. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 67(4):1323–1339 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Poon J, Buterin V (2017) Plasma: Scalable autonomous smart contracts, pp 283–295

- Praitheeshan P, Pan L, Yu J, Liu J, Doss R (2019) Security analysis methods on ethereum smart contract vulnerabilities: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.08605

- Regnath E, Steinhorst S (2018) Smaconat: Smart contracts in natural language. In: 2018 Forum on specification & design languages (FDL), IEEE, pp 5–16

- Reyna A, Martín C, Chen J, Soler E, Díaz M (2018) On blockchain and its integration with iot. challenges and opportunities. Future Gener Comput Syst 88:173–190 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rieth Y Payment systems: Visa vs. bitcoin. Available online at https://decenter.org/en/payment-systems-visa-vs-bitcoin (2018). Last accessed: 2020-10-10

- Rouhani S, Deters R (2019) Security, performance, and applications of smart contracts: A systematic survey. IEEE Access 7:50759–50779 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Saleh H, Avdoshin S, Dzhonov A (2019) Platform for tracking donations of charitable foundations based on blockchain technology. In: 2019 Actual problems of systems and software engineering (APSSE), IEEE, pp 182–187

- Schrans F, Eisenbach S, Drossopoulou S (2018) Writing safe smart contracts in flint. In: Conference companion of the 2nd international conference on art, science, and engineering of programming, pp 218–219

- Scoca V, Uriarte RB, De Nicola R (2017) Smart contract negotiation in cloud computing. In: 2017 IEEE 10Th international conference on cloud computing (CLOUD), pp 592–599

- Sergey I, Nagaraj V, Johannsen J, Kumar A, Trunov A, Hao KCG (2019) Safer smart contract programming with scilla. Proc. ACM Program. Lang 3(OOPSLA)

- Shariar A, Imran MA, Paul P, Rahman A (2020) A decentralized computational system built on blockchain for educational institutions. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing Advancements, ICCA. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, p 2020

- Shi F, Qin Z, Wu D, McCann J (2018) Mpcstoken: Smart contract enabled fault-tolerant incentivisation for mobile p2p crowd services. In: 2018 IEEE 38Th international conference on distributed computing systems (ICDCS), pp 961–971

- Shi N, Tan L, Li W, Qi X, Yu K (2020) A blockchain-empowered aaa scheme in the large-scale hetnet. Digital Communications and Networks

- Singh A, Parizi RM, Zhang Q, Choo KKR, Dehghantanha A (2020) Blockchain smart contracts formalization: Approaches and challenges to address vulnerabilities. Computers & Security 88:101654 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Singla V, Malav IK, Kaur J, Kalra S (2019) Develop leave application using blockchain smart contract. In: 2019 11Th international conference on communication systems networks (COMSNETS), pp 547–549

- Sirisha NS, Agarwal T, Monde R, Yadav R, Hande R (2019) Proposed solution for trackable donations using blockchain. In: 2019 International conference on nascent technologies in engineering (ICNTE), IEEE, pp 1–5

- TE-FOOD: Halal food companies are going to blockchain. Available online at https://cointelegraph.com/press-releases/halal-food-companies-are-going-to-blockchain (2018). Last accessed: 2020-10-01

- Team T. Truffle: Ethereum development framework. Available online at https://github.com/trufflesuite/truffle (2016). Last accessed: 2020-10-20

- Trotter L, Harding M, Elsden C, Davies N, Speed C (2020) A mobile platform for event-driven donations using smart contracts. In: Proceedings of the 21st International Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems and Applications. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, p 108

- Udokwu C, Kormiltsyn A, Thangalimodzi K, Norta A (2018) The state of the art for blockchain-enabled smart-contract applications in the organization. In: 2018 Ivannikov ispras open conference (ISPRAS), IEEE, pp 137–144

- Wang EK, Liang Z, Chen CM, Kumari S, Khan MK (2020) Porx: A reputation incentive scheme for blockchain consensus of iiot. Futur Gener Comput Syst 102:140–151 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wang H, Guo C, Cheng S (2019) Loc — a new financial loan management system based on smart contracts. Futur Gener Comput Syst 100:648–655 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wang P, Liu X, Chen J, Zhan Y, Jin Z (2018) Qos-aware service composition using blockchain-based smart contracts. In: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceeedings. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 296–297

- Wang S, Yuan Y, Wang X, Li J, Qin R, Wang F (2018) An overview of smart contract: Architecture, applications, and future trends. In: 2018 IEEE Intelligent vehicles symposium, IV 2018, changshu, suzhou, china, june 26-30, 2018, IEEE, pp 108–113

- Wang X, Yang W, Noor S, Chen C, Guo M, [van Dam] KH (2019) Blockchain-based smart contract for energy demand management. Energy Procedia 158:2719–2724. Innovative Solutions for Energy Transitions ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Watanabe H, Fujimura S, Nakadaira A, Miyazaki Y, Akutsu A, Kishigami JJ (2015) Blockchain contract: A complete consensus using blockchain. In: 2015 IEEE 4Th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE), IEEE, pp 577–578

- Westerkamp M, Victor F, Küpper A (2019) Tracing manufacturing processes using blockchain-based token compositions. Digital Communications and Networks

- WIRED: A 50 million hack just showed that the DAO was all too human. Available online at https://www.wired.com/2016/06/50-million-hack-just-showed-dao-human/ (2016). Last accessed: 2020-10-20

- Wright K, Martinez M, Chadha U, Krishnamachari B (2018) Smartedge: A smart contract for edge computing. In: 2018 IEEE International conference on internet of things (ithings) and IEEE green computing and communications (greencom) and IEEE cyber, physical and social computing (CPSCom) and IEEE smart data (smartdata), pp 1685–1690

- Xie W, Wang B, Ye Z, Wu W, You J, Zhou Q (2019) Simulation-based blockchain design to secure biopharmaceutical supply chain. In: Proceedings of the Winter Simulation Conference, IEEE Press, pp 797–808

- Xiong W, Xiong L (2019) Smart contract based data trading mode using blockchain and machine learning. IEEE Access 7:102331–102344 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Xu R, Lin X, Dong Q, Chen Y (2018) Constructing trustworthy and safe communities on a blockchain-enabled social credits system. In: Proceedings of the 15th EAI International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Systems: Computing, Networking and Services. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 449–453

- Xu X, Lu Q, Liu Y, Zhu L, Yao H, Vasilakos AV (2019) Designing blockchain-based applications a case study for imported product traceability. Futur Gener Comput Syst 92:399–406 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Yang Z, Lei H (2019) Fether: An extensible definitional interpreter for smart-contract verifications in coq. IEEE Access 7:37770–37791 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Yeh K, Su C, Hou J, Chiu W, Chen C (2018) A robust mobile payment scheme with smart contract-based transaction repository. IEEE Access 6:59394–59404 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Yu K, Tan L, Shang X, Huang J, Srivastava G, Chatterjee P (2020) Efficient and privacy-preserving medical research support platform against covid-19: A blockchain-based approach. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine

- Yu KP, Tan L, Aloqaily M, Yang H, Jararweh Y (2021) Blockchain-enhanced data sharing with traceable and direct revocation in iiot. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics

- Zhang F, Cecchetti E, Croman K, Juels A, Shi E (2016) Town crier: An authenticated data feed for smart contracts. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 270–282

- Zhang Y, Kasahara S, Shen Y, Jiang X, Wan J (2019) Smart contract-based access control for the internet of things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 6(2):1594–1605 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zhao S, O’Mahony D (2018) Bmcprotector: A blockchain and smart contract based application for music copyright protection. In: Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Application. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 1–5

- Zhao Y, Liu Y, Tian A, Yu Y, Du X (2019) Blockchain based privacy-preserving software updates with proof-of-delivery for internet of things. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 132:141–149 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zheng Z, Xie S, Dai HN, Chen W, Chen X, Weng J, Imran M (2020) An overview on smart contracts: Challenges, advances and platforms. Futur Gener Comput Syst 105:475–491 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zhou H, de Laat C, Zhao Z (2018) Trustworthy cloud service level agreement enforcement with blockchain based smart contract. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science (cloudcom), pp 255–260

- Zichichi M, Contu M, Ferretti S, DAngelo G (2019) Likestarter: A smart-contract based social dao for crowdfunding. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2019 - IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), pp 313–318

- Zou W, Lo D, Kochhar PS, Le XBD, Xia X, Feng Y, Chen Z, Xu B (2019) Smart contract development: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Shafaq Naheed Khan & Anoud Bani-Hani

- Univ. Polytechnique Hauts-de-France, LAMIH, CNRS, UMR 8201, F-59313, Valenciennes, France Faiza Loukil

- University of Lyon, iaelyon school of Management, University Jean Moulin Lyon 3, CNRS, LIRIS, Lyon, France Chirine Ghedira-Guegan

- Staffordshire University, Stoke on Trent, UK Elhadj Benkhelifa

- Shafaq Naheed Khan