Political debate and the anxiety it has fueled have created an unfortunate—and inaccurate—impression that trade agreements have destroyed manufacturing and are killing US jobs. A look at the facts reveals a more complex story and points to a different conclusion.

About This ReportThis report was prepared by Sean Randolph, Senior Director at the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. The Institute wishes to thank the many trade and economic experts who provided valuable insights and information, including Linda Dempsey, Vice President, International Economic Affairs, National Association of Manufacturers; Dorothy Dwoskin, Senior Director, Global Trade Policy and Strategy, Microsoft; Lisa Malloy, Director, Policy Communications, Intel; Matt Perault, Head of Global Policy Development, Facebook; Ken Monahan, Director for International Trade Policy, National Association of Manufacturers; and Chris Wall and Robert James, Partners, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman.

The Institute particularly wishes to thank the many organizations that supported this research: Bank of the West, DLA Piper, HSBC, Intel, Microsoft, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman, the Port of Oakland, San Francisco International Airport, Visa, and Wells Fargo.

On balance, free trade agreements have benefited the United States, and US workers. This is true of both bilateral and multilateral agreements. These agreements have been negotiated by the US to advance US interests, and accordingly reflect US values and objectives. They also reflect an alignment of interests with our negotiating partners, who similarly benefit from growing trade. Contrary to what some have asserted, there is no evidence that bilateral agreements are inherently superior to multilateral ones, or that free trade agreements have been abused or manipulated by our partners. By virtue of their scale, multilateral agreements can in fact deliver strategic benefits to the US that bilateral ones may not.

Since the 1980s, both bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs) have been used by nations around the world to reduce barriers, open markets, and create new and higher standards in areas such as investment, intellectual property, and now digital commerce. Behind the US approach to trade agreements has been a recognition that as global markets grow in importance and emerging markets expand, trade and investment opportunities grow as well.

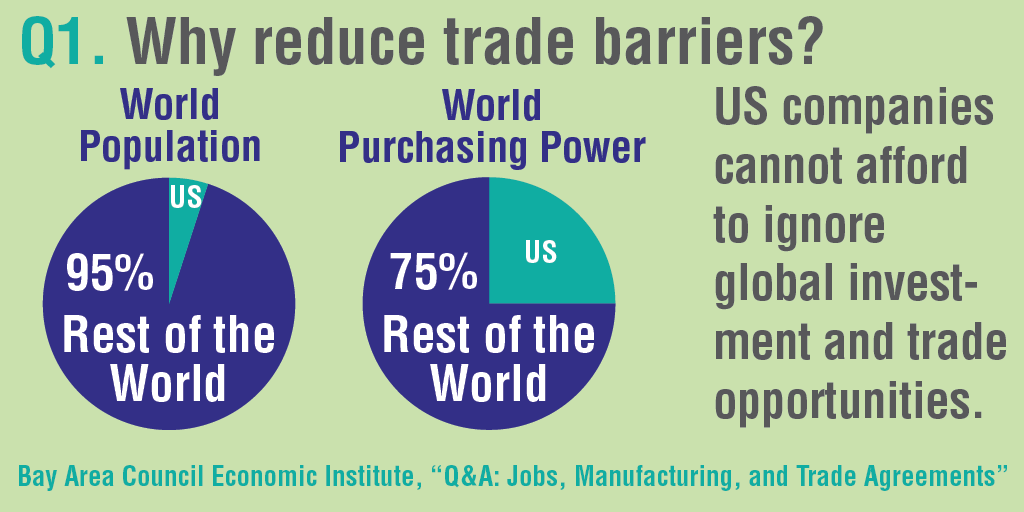

The collapse of communism, the entry of China and India into the world economy, and accelerating growth in Asia and other regions have brought billions of new consumers into the global market economy. That includes hundreds of millions of consumers who have entered the middle class with new purchasing power. By reducing trade and investment barriers, leaders across multiple administrations have believed that markets overseas will expand, due to the lowering of barriers but also due to growing trade volumes. US companies cannot afford to ignore these opportunities, as 95 percent of the world’s population and 75 percent of global purchasing power now reside outside the United States.

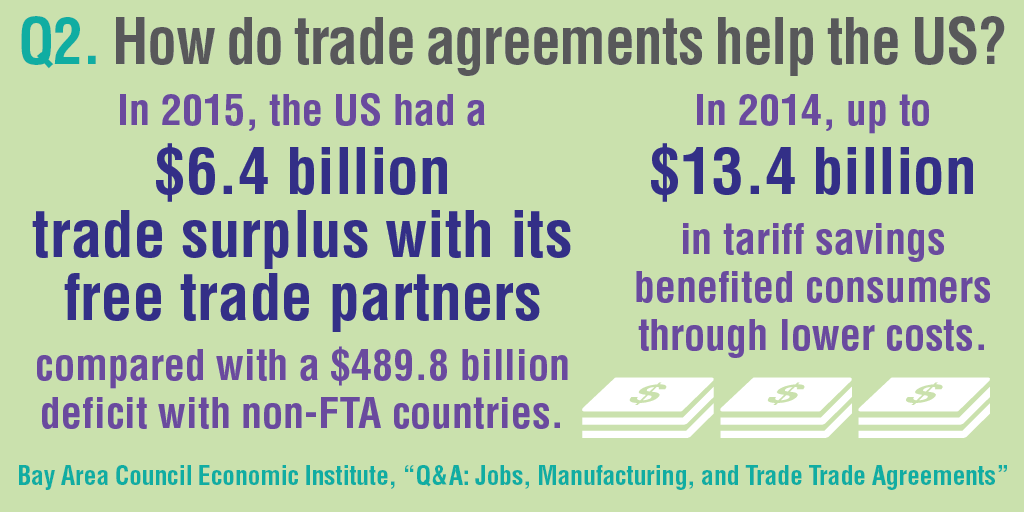

Multiple assessments have shown that free trade agreements have clear benefits for the United States. US International Trade Commission economic analysis models have found that in addition to positively affecting real GDP, employment, and wages, FTAs currently in force increased US trade surpluses or reduced trade deficits with partner countries by 59.2 percent ($87.5 billion) in 2015. They also produced tariff savings of up to $13.4 billion in 2014 , benefiting consumers—particularly those with low or middle incomes—through lower costs.

Of the 267 bilateral and regional free trade agreements that have been negotiated around the world, only 14 involve the United States. The provisions included in the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an agreement between the United States and 11 trading partners, were positioned as the centerpiece of US strategy both to open markets and cement US economic leadership in the Asia-Pacific region. The withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership will not stop this global process. Canada and the European Union have recently approved a free trade agreement, and Japan and Europe are discussing one. In Asia, China’s proposed 16-nation trade agreement—RCEP—is positioned to fill the void left by the US withdrawal.

Taken together, nearly half of all US-manufactured exports are purchased by free trade agreement partners, even though they account for only 6 percent of the world’s consumers and less than 10 percent of the world’s economy. In 2015, the US enjoyed a $6.4 billion goods and services surplus with its 20 free trade partners, compared with a $489.8 billion deficit with non-FTA countries. Currently, the United States’ largest trade deficit is with China, which has no trade agreement with the US and was not a party to the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Contrary to critics’ claims, trade agreements are not the fundamental cause of erosion in the US manufacturing sector or of the disappearance of manufacturing jobs. Manufacturing output is growing, and US manufacturing companies produced a record $2.2 trillion in value in 2015. Manufacturing production, however, is different from employment, which has been declining for decades. Only a small part (approximately 13 percent) of that decline is due to trade. The real reason we have fewer manufacturing jobs is technology, which makes production more efficient and requires fewer workers. An instructive parallel is agriculture, where US production since 2010 is up 13 percent, while jobs in agriculture fell 15 percent, both trends due to technology. These are inexorable processes that will continue.

Free trade agreements have, in fact, had a positive impact on manufacturing. In 2015, US manufacturers sold $12.7 billion more in manufactured goods to FTA partners than US companies bought from them. At the same time, the US had a manufacturing trade deficit of $639.6 billion with countries where no FTAs are in place.

The United States could have expected similar benefits from the Trans-Pacific Partnership. While the US has officially withdrawn from that agreement, it could still benefit from successor agreements with similar terms.

The US International Trade Commission estimated that with TPP, exports to TPP partners would have grown faster than exports to other countries. Imports from TPP partners would also have grown, but not as fast as exports. Regarding employment, the Peterson Institute for International Economics estimated that the agreement would have raised real US wages but would not have significantly changed overall employment levels.

“Job churn,” the movement of jobs between firms, sectors, and industries, was projected by the Peterson Institute model to be 53,700 annually, including both jobs eliminated in less productive import-competing firms and jobs added in firms that expand. Experience demonstrates that the resulting jobs, in both manufacturing and services, are better paying than jobs in companies that do not compete globally. The great majority of these jobs are for middle-class Americans who produce and move the goods and generate the services.

While manufacturing is a major focus in trade debates, services are also important: tradable business services (including legal services, consulting, financial services, accounting, architecture, engineering, healthcare, and education) account for 25 percent of US employment—double the share of manufacturing. The service economy is growing fast, and the Peterson Institute projects that 90 percent of US workers will be employed in the service sector by 2030. In contrast to trade in goods, the US enjoys a sizable trade surplus in services.

The principles and provisions contained in TPP significantly benefit large and small companies across a range of sectors. Technology companies and their workers would benefit through the opening of service markets, the strengthening of intellectual property protection, the protection of the cross-border movement of data, and the protection of source code from expropriation by foreign governments. Agriculture would also benefit, as once-restricted markets such as Japan’s would open to US exports. In other areas of interest, TPP’s provisions included enforceable labor and environmental protections, setting the highest standards of any international trade agreement to date.

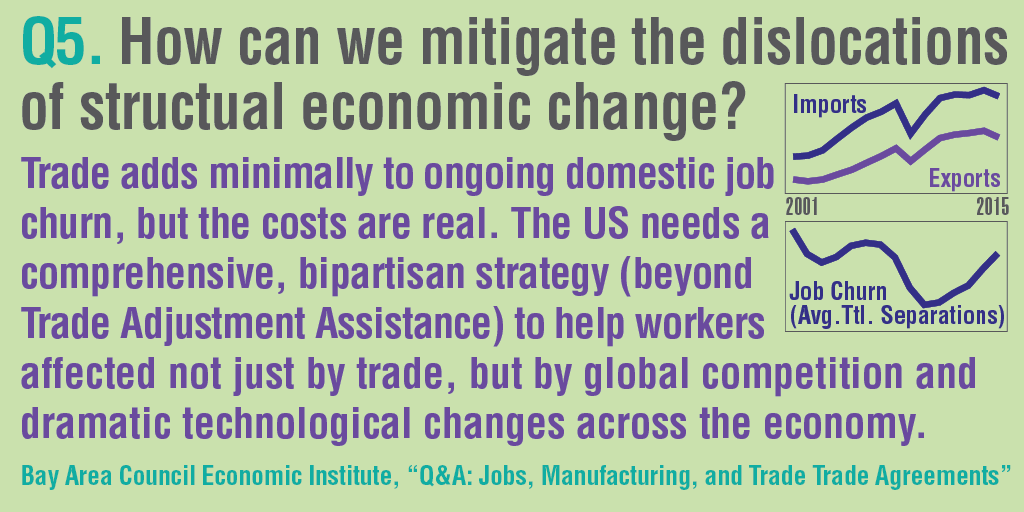

Despite the formal withdrawal of the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the principles that it advanced would produce net benefits for the economy and for American workers. There is no doubt that trade contributes to economic churn, as less competitive jobs decline and more competitive ones grow. Many more Americans stand to gain in this process than lose. For those who lose, however, the pain is real. In response, we should overhaul Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA), the federal program that provides transitional help toward new employment for dislocated workers. Beyond that, our country needs a comprehensive, bipartisan strategy for how to transition workers who are affected not just by trade, but by global competition and the dramatic changes that technology is producing across the economy.

Anxiety that trade agreements are responsible for these dislocations is misplaced. The evidence is compelling that California and the nation, through competitive companies and their workers, benefit from more open trade. Addressing the dislocations caused by global competition and the technology-driven changes that are transforming both industries and jobs—changes that are not caused by trade agreements—is an important and complex task that should be on the national agenda. But the US should not back away from trade agreements or abdicate its role as the leading global advocate for free and open markets.

Behind the US approach to trade agreements has been a recognition that as global markets grow in importance and emerging markets expand, trade and investment opportunities grow as well.

Economic modeling indicates that free trade agreements (FTAs) positvely affect real GDP, employment, and wages, and that FTAs currently in force have increased trade surpluses or reduced trade deficits with partner countries.

Contrary to critics’ claims, trade agreements are not the fundamental cause of erosion in the US manufacturing sector or of the disapppearance of manufacturing jobs. Manufacturing output is growing, but manufacturing production is different from employment, which has been declining for decades. However, only about 13 percent of that decline is due to trade. The real reason we have fewer manufacturing jobs is technology, which makes production more efficient and requires fewer workers.

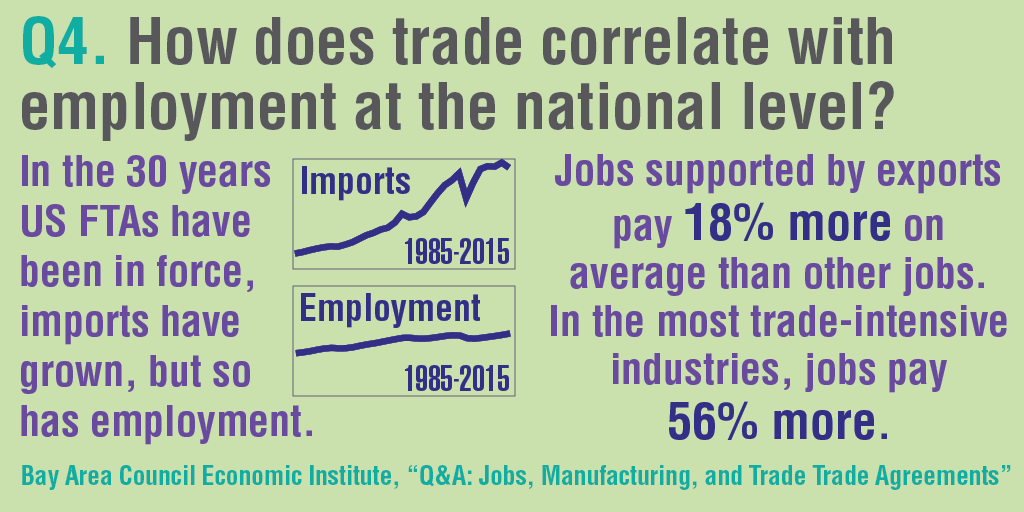

Overall, at the national level, the existence of trade agreements does not correlate with job loss. What is very clear is the benefit that manufactured exports bring to the economy. Exports support higher-paying jobs for an increasingly educated and diverse middle class workforce.

Trade agreements help the US leverage comparative advantage, but the process does contribute to “job churn,” as less competitive jobs decline and more competitive ones grow. Many more Americans stand to gain in this process than lose, but for those who lose, the pain is real. It is important, therefore, that government and private sector leaders begin a long-term conversation not just about trade, but about the structural changes under way in the economy that will impact competitiveness and employment on a much larger scale.

[flipbook pdf=”https://www.bayareaeconomy.org/files/pdf/RealImpactOfTradeAgreements.pdf” header=”Opening the report…” lightbox=”true” cover=”https://www.bayareaeconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/RealImpactOfTradeAgreementsFrontCover1280.png”]

Click the cover image to begin reading the interactive online report.